To put it simply, students entering this competition were asked to reimagine Interstate 95, as it runs along the east shore of Philadelphia next to the Delaware River, effectively cutting off the public from the River and its surroundings and creating countless other problems. Here is how some Temple students responded.

Plug - In

This group, winning the competition's sustainability category, imagines the highway as a source of energy:

Plug-In redesignes I-95 as a generator of electrical energy to nearby homes, businesses and vehicles by harnassing wind, elctro-kinetic, and piezolectric power.

The new I-95 will supply electricity to the parks and walking districts above it, as well as cover 50% of the elctric cost to those who wat to build on the vacant/underused lots of the area.

- by Melhissa Carmona, Noelle Charles, Amanda Mazid.

The Death and Life of Great American Highways

Here's a group who proposed leaving the Highway to rot:

Historical studies reveal a pattern of death and life - pavement taking over forest, retail rising out of industry, highways emerging out of railroad ruins... the pattern will continue ad infinitum. The highway typology will see its imminent death with the decline of oil production. Any infrastructure linked to the highway and oil use will die off: parking lots will become increasingly vacant, big box retail will decline as importing becomes scarcer, and also areas of the city will be swallowed by the rising waters of the Delaware. The city will soon search for a new way of living in the ashes of the obsolete past.

Plug - In

This group, winning the competition's sustainability category, imagines the highway as a source of energy:

Plug-In redesignes I-95 as a generator of electrical energy to nearby homes, businesses and vehicles by harnassing wind, elctro-kinetic, and piezolectric power.

The new I-95 will supply electricity to the parks and walking districts above it, as well as cover 50% of the elctric cost to those who wat to build on the vacant/underused lots of the area.

- by Melhissa Carmona, Noelle Charles, Amanda Mazid.

The Death and Life of Great American Highways

Here's a group who proposed leaving the Highway to rot:

Historical studies reveal a pattern of death and life - pavement taking over forest, retail rising out of industry, highways emerging out of railroad ruins... the pattern will continue ad infinitum. The highway typology will see its imminent death with the decline of oil production. Any infrastructure linked to the highway and oil use will die off: parking lots will become increasingly vacant, big box retail will decline as importing becomes scarcer, and also areas of the city will be swallowed by the rising waters of the Delaware. The city will soon search for a new way of living in the ashes of the obsolete past.

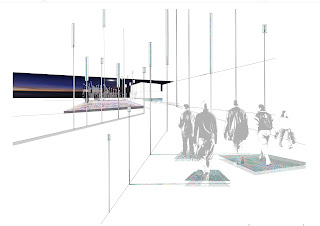

Various magnitudes of 'cracks' exist in the area. Our proposals will strengthen and expand these cracks, allowing natural forces and multifunctional elements to seep through, thus revitalizing dead infrastructure with diversity of function.

A new I-95 will be obsolete in as little as 40 years, and is therefore a waste of the city's funds. The current I-95 will be repaired as it is, with minor adjustments that will urge the highway to decay gracefully. As traffic volum decreases, natural elements (trees, streams, wetlands) will appear in cracked areas.

Differing sections of the decayed I-95 will include: freshwater reservoir, wetlands (providing water filtration). young and old forests, farmlands, hills, recreational areas, and shelters for the environmentally displaced.

- by Carolina Giraldo, Ian Sauls, Brandon Youndt.